“A Fortress Besieged By An Invading Army”: The Astor Place Riot

Posted by Judith Maas on Apr 12th 2020

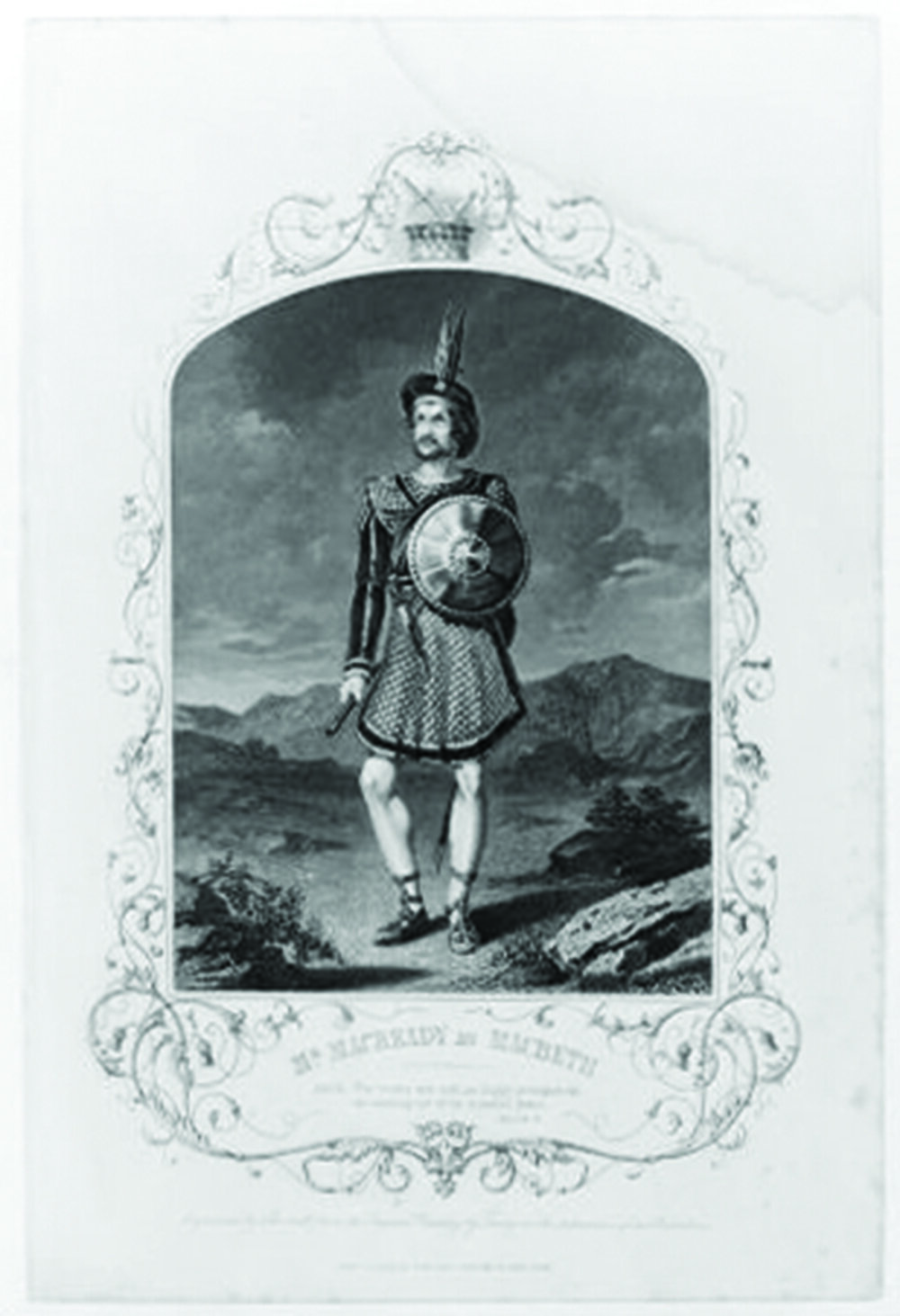

On the evening of May 10, 1849, the British Shakespearean actor William Charles Macready, playing Macbeth, stepped onto the stage of the palatial Astor Place Opera House in lower Manhattan. Built in 1847, the theater had been named for business mogul John Jacob Astor, the richest man in America. Macready, admired for his refined, studious approach to acting, received a standing ovation from the mostly well-to-do theater patrons.

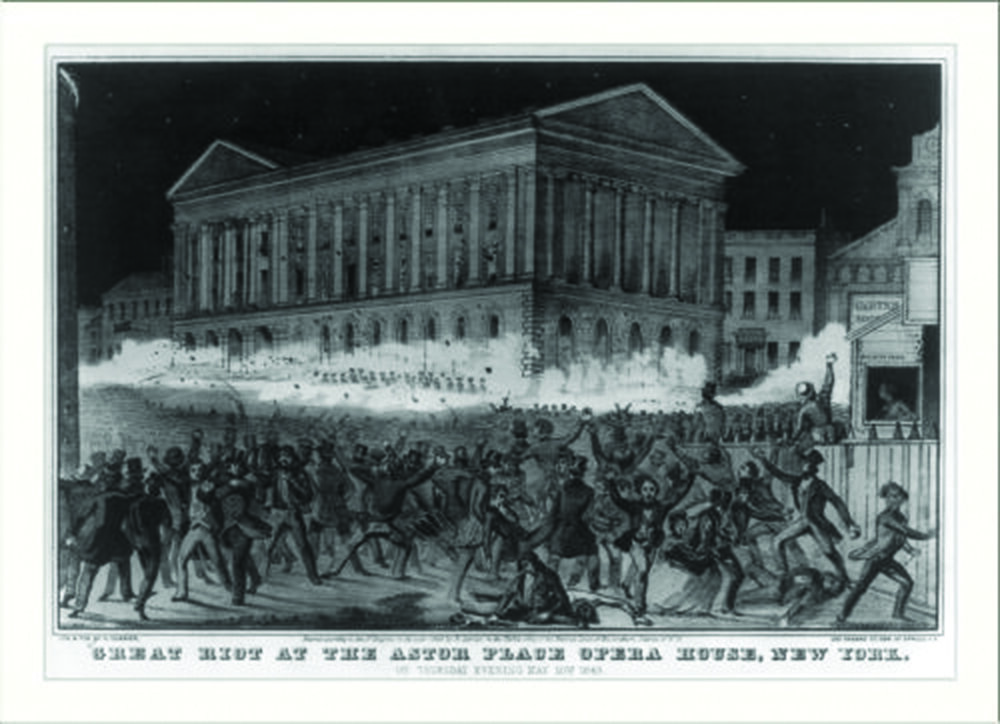

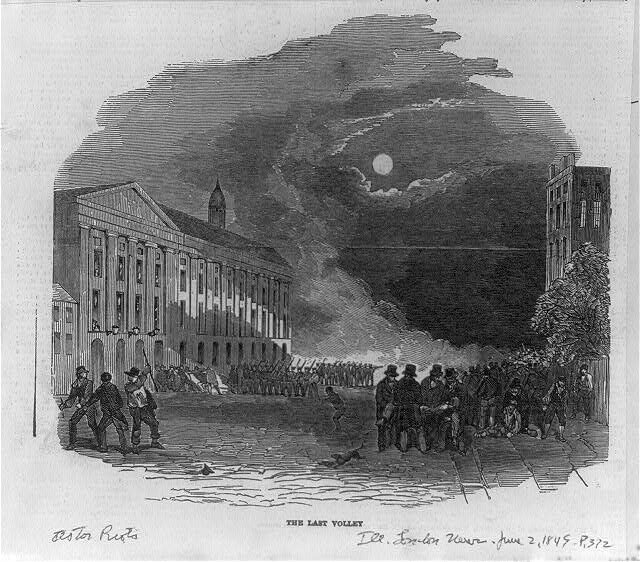

Meanwhile outside, thousands of workingmen and street gang members hurled bricks and paving stones at the building, egged on by such cries as “You can’t go in there without … kid gloves and a white vest, damn ’em!”[1] The protesters were supporters of Macready’s Shakespearean rival, the American Edwin Forrest, beloved for his bold, energetic acting style. As the violence escalated, the National Guard fired into the crowd. By evening’s end, at least twenty-two people were dead and many others wounded. According to one press account, “the Opera House resembled a fortress besieged by an invading army rather than a place meant for the peaceful amusement of a civilized community.”[2]

The enmity between the two actors, and their followers, had been long in the making. Macready (1793-1873) was born in London, the son of a theater manager whose financial troubles had cut short William’s education and forced him, against his wishes, into a career on the stage. He made his debut in 1810, starring in Romeo and Juliet, and would go on to perform at Covent Garden and Drury Lane, playing such roles as Othello, Richard III, Lear, and Macbeth. Despite achieving wealth, popularity, and acclaim, he harbored a lasting bitterness toward his profession and became known for his haughty behavior.

Forrest (1806-1872), born in Philadelphia to a poor family, was the proverbial self-made man. He learned his craft by attending theater performances, studying elocution, and touring in the provinces with an acting company. His break came in 1826, when he debuted in New York as Othello. His appeal to critics and audiences lay in his good looks, deep voice, and lack of gentility. As one observer put it, “He possessed a fine untaught face and good manly figure and, though unpolished in his deportment, his manners were frank and honest, and his uncultivated taste, speaking the language of truth and nature, could be readily understood.”[3] He became enormously popular and wealthy and was touted in the press as the “American Tragedian,”[4] an implicit protest against the large number of British actors appearing in the States. Beginning in 1828, Forrest burnished his patriotic credentials by sponsoring playwriting contests for American dramatists writing on native subjects.

Macready and Forrest crossed paths, amicably, in 1836, when Forrest first performed in London. Returning in 1845, he received negative reviews from a critic who happened to be a friend of Macready. Forrest blamed Macready and in retribution hissed during a Macready performance of Hamlet in Edinburgh; in a letter to the London Times, he defended his conduct, describing hissing as “a salutary and wholesome corrective of the abuses of the stage.”[5] The incident drew press attention, and by the time Macready came the United States for his third tour in 1848, a storm was brewing: Forrest began to tail Macready, performing the same plays in the same cities; the press chimed in to support Forrest, accusing Macready of “mercenary motives”;[6] a satirical play was mounted in New York entitled Mr. McGreedy.[7]

On May 7, 1849, Forrest and Macready both played Macbeth in New York. Macready’s Astor performance had to be shut down during the third act, as audience members in the upper galleries pelted him with vegetables, eggs, coins, blocks of wood, and chairs.[8]

The press weighed in, and New Yorkers took sides, mainly along class lines. Prominent writers, including Washington Irving and Herman Melville, signed a letter urging Macready to give another performance at the Astor. Forrest partisans, some of whom were active in nativist circles, recruited demonstrators and posted signs appealing to patriotism and class interests: “Workingmen, shall Americans or English rule in this city?... Washington forever! Stand by your Lawful Rights.”[9] And so the battle lines for the evening of May 10 were drawn.

Class antagonisms, patriotism, nativism, anti-British sentiment, the cult of celebrity, the power of the press -- all fueled the Astor Place riot. What seems most strange today is that Shakespeare, the premier English writer, would prove a touchstone for American working-class and national pride. The first known performance of a Shakespeare play in America took place in 1750. From then onward, Shakespeare was increasingly Americanized, adapted to suit a variety of needs, aspirations, and pleasures.[10]

Thomas Jefferson and John and Abigail Adams turned to Shakespeare for political guidance—in a letter, Abigail Adams compared King George III with Shakespeare’s Richard III; Jefferson took a special interest in plays, such as Julius Caesar, dealing with problems of authority. A newspaper parody of Hamlet from the 1770s asked, “Be taxt or not be taxt—that is the question.”[11] During the early nineteenth century, Shakespeare’s works became part of the fabric of American life, but not in ways that are familiar to us. At a time when great sermons and speeches were highly esteemed, Shakespeare was taught in schools as rhetoric rather than as literature. The plays were performed in all kinds of unlikely venues: flatboats, steamboats, shops, hotels, churches, breweries, above saloons, and in mining camps. In theaters, Shakespeare was performed alongside magicians, singers, and acrobats, sometimes in the form of scenes or monologues.[12]

Performances drew audiences from different classes and backgrounds.[13] Describing an evening at the Bowery Theater in 1840, Walt Whitman captured the diversity of the crowd: in the first tier of box seats, he saw “the faces of the leading authors, poets, editors” of the day and in the pit he found “slang, wit, occasional shirt sleeves, and a picturesque freedom of looks and manners, with a rude good-nature and restless movement of workers.”[14] In her 1832 book, Domestic Manners of the Americans, British visitor Frances Trollope had characterized Americans, including theatergoers, as loud, vulgar, and boorish. Loyalty to an Edwin Forrest and his boisterous Shakespearean performances represented defiance and mockery of old rigidities, an assertion of self-respect, and the claiming of an American identity.

Shakespeare in America had belonged to everybody, or so it seemed. But the Astor Place riot brought with it condemnation of Forrest and his supporters. The freewheeling spirit of the theater began to dissipate, and cultural changes emerged that seem much more akin to our own times: a schism between popular and highbrow entertainment; the rise of exclusive theaters for upper-class audiences; and the association of Shakespeare with erudition and high art.[15]

[1] Lawrence W. Levine, “William Shakespeare and the American People: a study in cultural transformation,” American Historical Review, 89:1 (Feb. 1984), 61.

[2] Richard Moody, The Astor Place Riot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1958), 140.

[3] Lloyd Morris, Curtain Time: the story of the American theater (New York: Random House, 1953), 86.

[4] “Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New-York Astor Place Opera House” in James Shapiro, ed., Shakespeare in America: an anthology from the Revolution to now (The Library of America, 2014), 67.

[5] Ibid., 68.

[6] Ibid., 73.

[7] Frances Teague, Shakespeare and the American Popular Stage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 55.

[8] For an overview of the seating arrangements at the Astor, see Teague, 55-56.

[9] Morris, 100.

[10] See Levine; Teague; Alden T. Vaughan and Virginia Mason Vaughan, Shakespeare in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); and Shapiro, “Introduction,” xix-xxxi.

[11] Teague, 25-26, 24.

[12] Levine, 50, 38-39, 42.

[13] Levine, 40, 42.

[14] Levine, 43.

[15] Levine, 58-60, 62-64; Vaughan, 44.