Jane Addams, George Pullman, and King Lear

Posted by Judith Maas on Apr 17th 2020

The career of Jane Addams (1860-1935) was bracketed by the founding of the Chicago social settlement, Hull House, in 1889, and her receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Her list of accomplishments is daunting: she helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom; she wrote books and articles on social reform and spoke at home and abroad on behalf of her views.

And throughout, she lived and worked at Hull House, located in a poor immigrant neighborhood. The settlement’s programs and services were vast: classes, an art gallery, a gymnasium, a swimming pool, a library, an employment bureau, a health clinic, a meeting place for trade union groups, a boardinghouse for working girls, and art, music, and theater clubs. Addams and her colleagues fought for garbage collection, child labor reform, consumer rights, and public education.

Schoolchildren have dutifully learned about Jane Addams and Hull House. But her long-time stature as a textbook heroine has obscured the depth and range of her thinking and the doubts and struggles she experienced. Since the late twentieth century, scholars have begun to recognize Addams as a contributor to the American school of pragmatism, aligning her with philosophers William James and John Dewey.[i] Biographers have studied how she became Jane Addams, exploring her privileged background as the daughter of a politician and businessman, her family relationships, her agonized search for a vocation after college, and the challenges she faced in working out a role for Hull House.[ii]

Addams believed that progress emerged through cooperation. The Pullman strike of 1894 would test her faith in that ideal, particularly when company president George Pullman rejected outright her efforts to engage him in arbitration talks. As the tensions between workers and the company escalated, and as Addams gamely “maintained avenues of intercourse with both sides,”[iii] she and Hull House came under attack from all sides; strikers wanted a stronger commitment to their cause, while the city’s affluent denounced Addams as a “traitor to her class”[iv] and ceased making donations to Hull House.

Reflecting on the conflict in its aftermath, Addams sought guidance from a surprising source: a play written in 1605-6 and set in ancient times‒Shakespeare’s King Lear. In a speech published many years later as an essay, she drew an analogy between George Pullman, the benevolent autocrat, and King Lear, the self-regarding ruler and father, and between the striking workers and Lear’s daughter Cordelia.

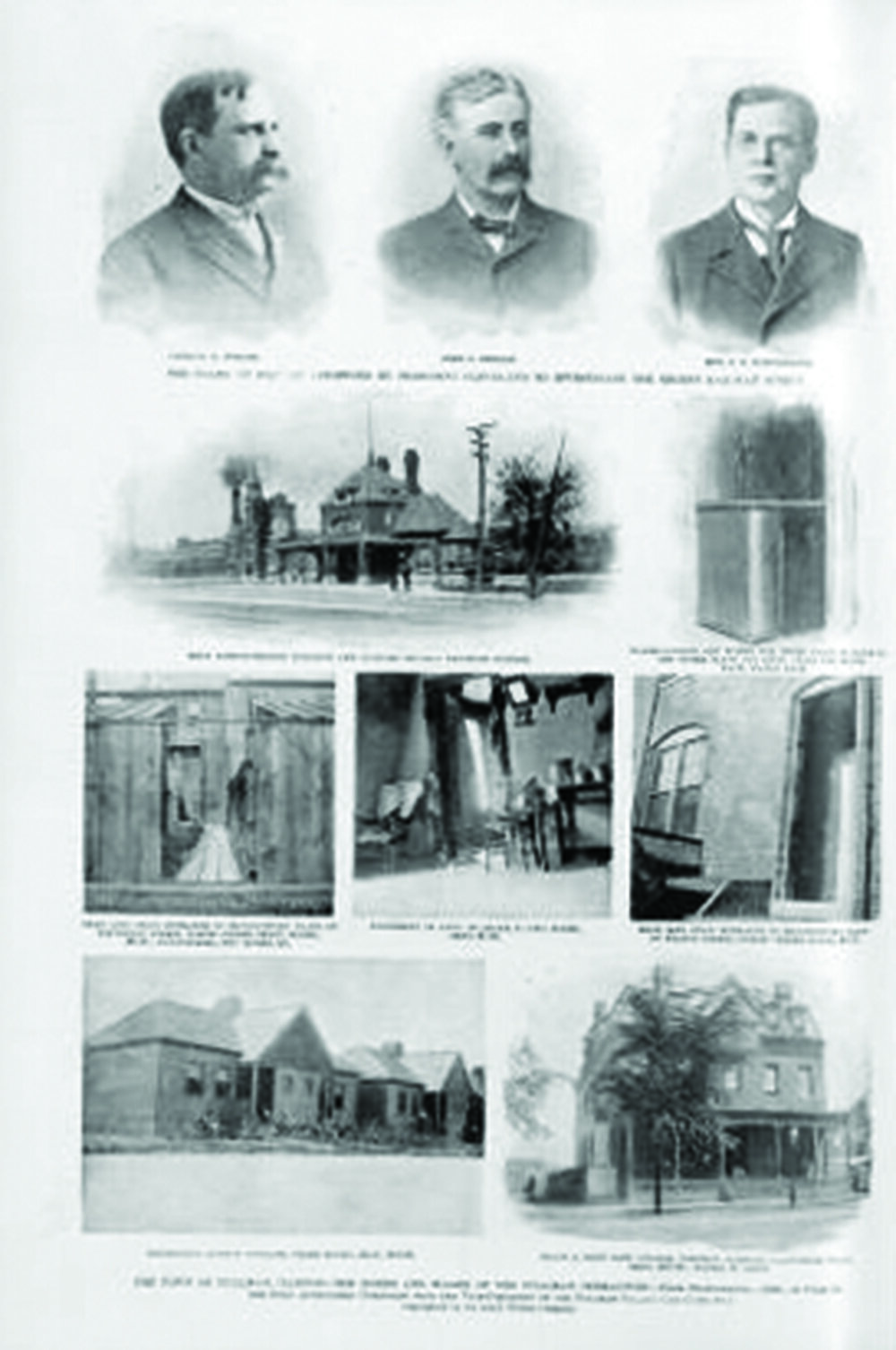

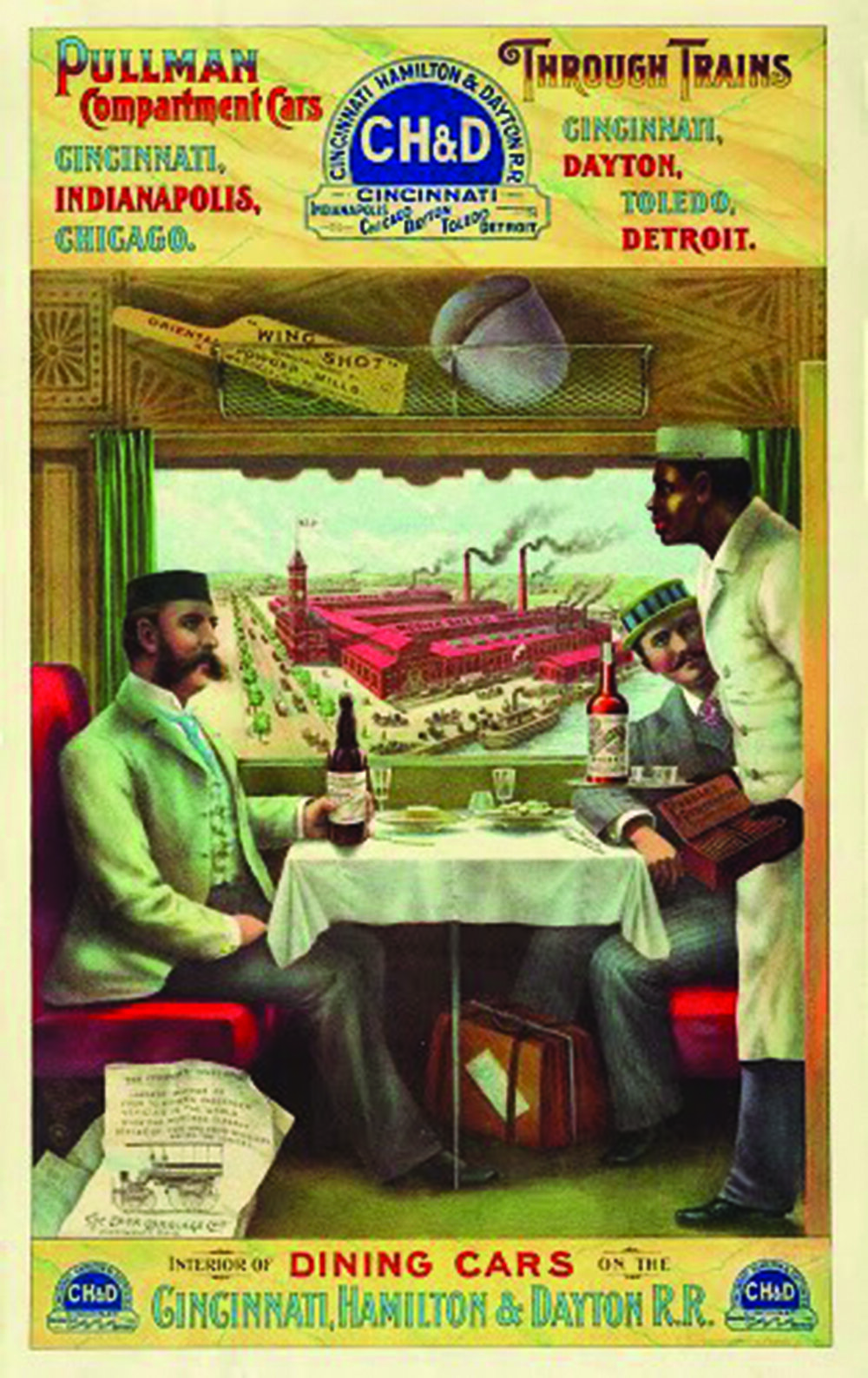

The model industrial town of Pullman, located south of Chicago and completed in 1884, was the brainchild of Pullman, whose Pullman Palace Car Company made luxury railway sleeping cars. Employees residing in the town enjoyed clean, modern housing; daily garbage collection; parks and tree-lined streets; and a library, a theater, a bank, and shops. Pullman wanted to create a setting in which “all that would promote the health, comfort, and convenience of a large working population would be conserved, and…many of the evils to which they [laborers] are ordinarily exposed [are] made impossible.”[v] He also, no doubt, expected the workers’ loyalty and productivity.

The material benefits, however, came with a steep price, fueling worker resentment. The company controlled all aspects of town life: It owned the houses, settled disputes, ran the newspaper, prohibited alcohol, stocked the library, chose the entertainment, and planted spies. Writing in Harpers in 1885, the economist Richard Ely observed, “The power of Bismarck in Germany is utterly insignificant when compared with the power of the ruling authority of the Pullman Palace Car Company in Pullman.”[vi]

In the wake of the 1893 depression, Pullman laid off workers and reduced wages while refusing to reduce rents. Some families faced starvation, even as the company continued to pay out shareholder dividends.[vii] Led by the American Railway Union (ARU), a cross-trades union founded by Eugene Debs, Pullman workers went out on strike in May 1894. “We struck at Pullman,” stated a worker, “because we were without hope.”[viii]

The Civic Federation of Chicago, a group of community leaders, hoped to forge a settlement. Under its auspices, Addams sought to bring the strikers and the company representatives into arbitration. While the workers were receptive, the company’s position remained adamant: there was nothing to arbitrate. In June, the ARU voted to begin a national boycott of Pullman cars, the largest display of union strength the nation had yet seen.[ix] During July, under orders from President Grover Cleveland, armed federal troops entered the city, leading to violent confrontations, and by August, the Pullman workers were defeated.

For Addams, these events raised difficult questions, not only about the immediate issues but also about the enduring relationship between workers and owners: What are the limits of benevolence, and why did it fail? Is there an alternative to conflict? What do bosses and workers owe one another?

“A Modern Lear,” composed in 1895, is Addams’s attempt to draw lessons from the strike. Though she affirms her support for the workers’ goals, the essay is not a political tract. Through the characters of Lear and Cordelia, Addams seeks to distill “the deep human motives” behind the conflict. She portrays Pullman as flawed rather than evil. Like Lear, he wants to be esteemed for his largess and to conduct relationships on his own terms. Proud of his generosity, he does not recognize the needs and desires of his workers and takes their independence as a personal affront. His failure is one of vision and imagination: “He did not see the situation…. A movement [toward justice] had been going on about him and through the souls of his workingmen of which he had been unconscious.” Addams even tries to see matters from Pullman’s perspective, suggesting that in the context of his times, he was a liberal employer honestly trying to do good. But, pragmatic in her outlook, she adds, “The virtues of one generation are not sufficient for the next.” In Cordelia, Addams sees a young woman reaching toward a “fuller life,” as were the Pullman workers, but also observes a “lack of tenderness” in her treatment of her father; the workers, Addams proposes, cannot abandon the “old relationships,” but must be “inclusive of the employer” in their pursuit of justice. The employer, in turn, must move “with the people,” and “discover what people really want.”

Addams’s even handedness won her few allies. The essay was not published until 1912, because no journal editor would accept it. Addams sometimes exasperated even her colleagues. Hull House co-founder Ellen Gates Starr said of her, “if the devil himself came riding down Halsted Street with his tail waving out behind him, [Jane Addams would say] what a beautiful curve he had in his tail.”[x] Despite the scorn that greeted her efforts to mediate the strike, Addams did not retreat into bitterness. Instead, in the spirit of Shakespeare, she used the experience as an opportunity to explore human nature. Unlike the conventional specialist or expert, she writes about people and relationships rather than numbers and categories. Her essay exemplifies what scholars view as a cornerstone of her philosophy: sympathetic knowledge, or the idea that “good citizens actively pursue knowledge of others—not just facts but a deeper understanding—for the possibility of caring and acting on their behalf.”[xi]

[i] See works by Maurice Hamington: The Social Philosophy of Jane Addams (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009); “Jane Addams,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) and “Jane Addams,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

[ii] Victoria Bissell Brown, The Education of Jane Addams (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Louise W. Knight, Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

[iii] Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House (New York: New American Library, 1910, 1938), 158.

[iv] Knight, Citizen, 319.

[v] “The Pullman Era,” Chicago Historical Society

[vi] Richard T. Ely, “Pullman: A Social Study,” Harper's Magazine 70 (February 1885): 452-466.

[vii] Knight, Citizen, 309.

[viii] Quoted in Ibid., 309.

[ix] Knight, Citizen, 316.

[x] Quoted in Victoria Brown, “Advocate for Democracy: Jane Addams and the Pullman Strike,” in The Pullman Strike and the Crisis of the 1890s, edited by Richard Schneirov, Shelton Stromquist, and Nick Salvatore (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 147.

[xi] Hamington, “Jane Addams,” Stanford Encyclopedia.