The American Library Association’s Library War Service

Posted by Judith Maas on Apr 9th 2020

“In the ability to reach, educate and affect the adult population the library occupies a position of great responsibility and is a great power for national defense.”

- Charles B. Alexander, speech to the annual meeting of the American Library Association (ALA), September 1918[i]

Addressing his colleagues, Charles B. Alexander linked together terms we usually don’t expect to find in one sentence: “the library” and “national defense.” He was referring, proudly, to the ALA’s Library War Service, a program begun in 1917 to give soldiers at home and overseas access to books, magazines, and newspapers. Newly mobilized librarians had to train themselves to become master organizers, fundraisers, publicists, and dispatchers.

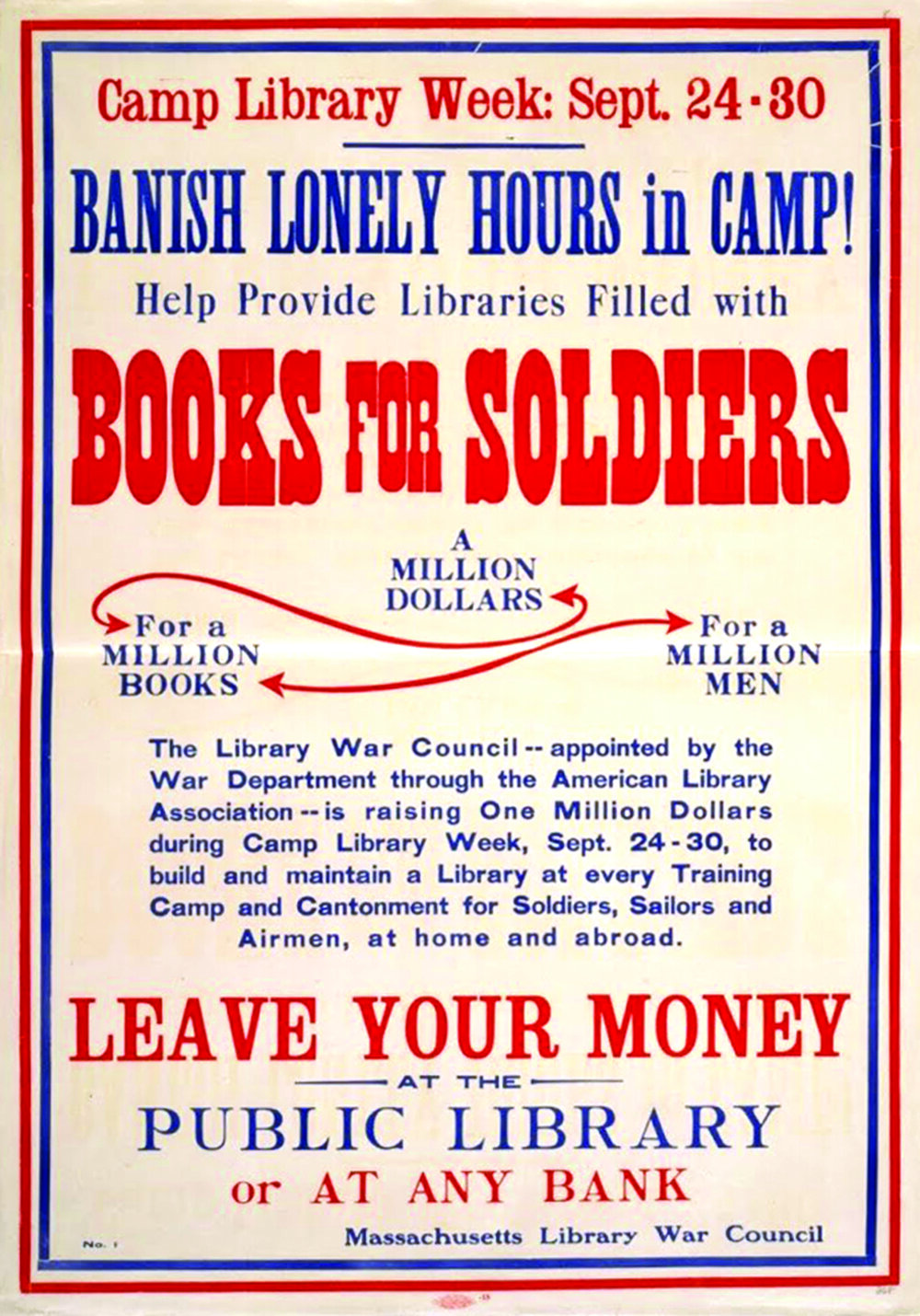

And they succeeded. By 1920, the ALA had raised $5 million from the public and $320,000 from the Carnegie Corporation to build 36 camp libraries. Individuals, libraries, authors, and publishers responded to three book drives. In the end, ten million volumes would be distributed to soldiers, with money set aside to purchase books and subscriptions. Nearly 1,200 people worked in the libraries established by the program, including some in military hospitals.[ii]

The ALA launched the program at the invitation of the U.S. War Department’s Commission on Training Camp Activities. It afforded the then-obscure association an opportunity to gain visibility and demonstrate the value of libraries to society. Founded in 1876, the ALA had been a small, inward-looking organization, with 3,300 members and an annual budget of $24,000. “[It] was merely a humdrum professional organization, wrapped round with tradition, settled in its habits of thought, and chiefly occupied with matters of technical detail,” said one member.[iii] Another recalled an occasion on which “ALA” was thought to stand for “American Laundry Association.”[iv]

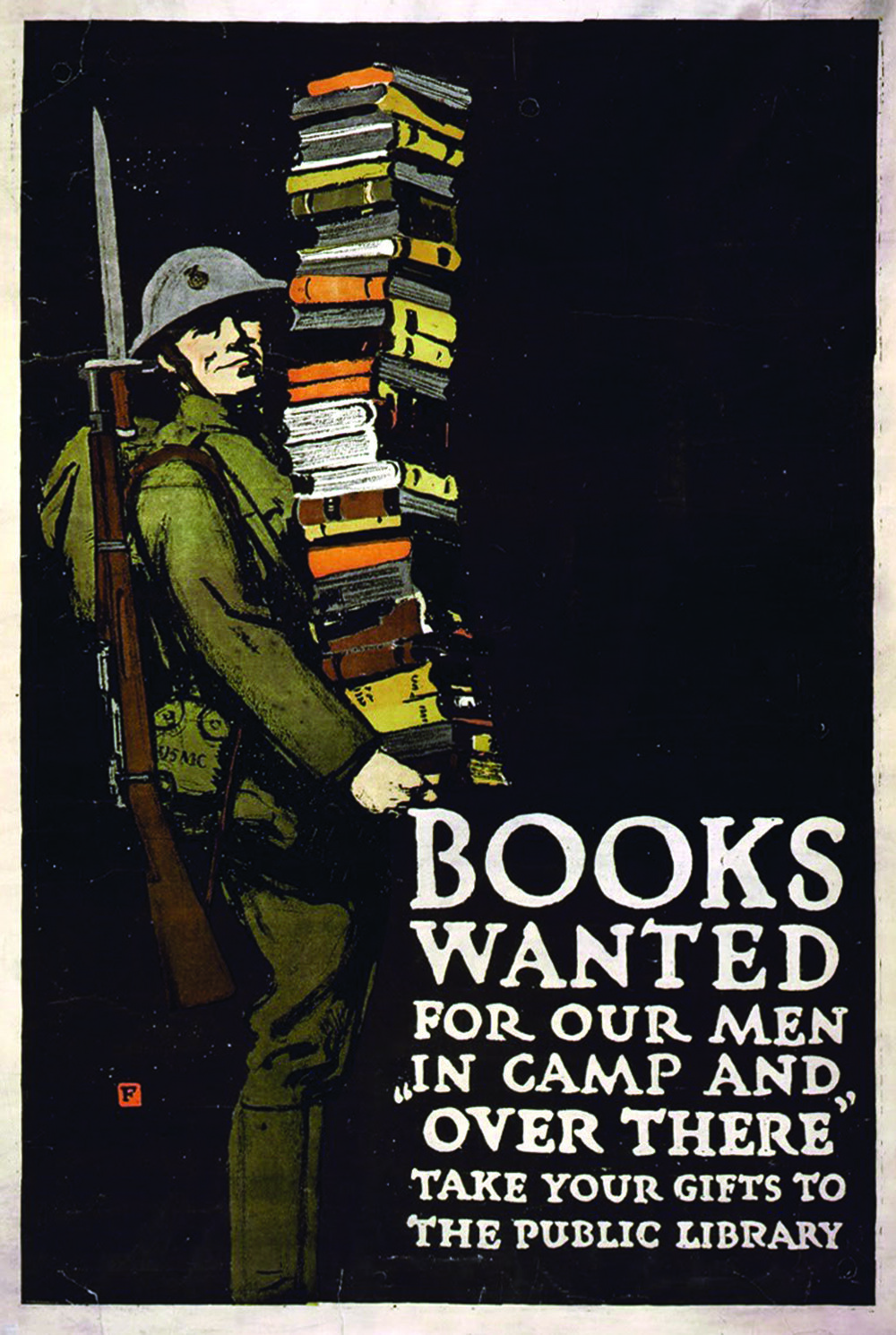

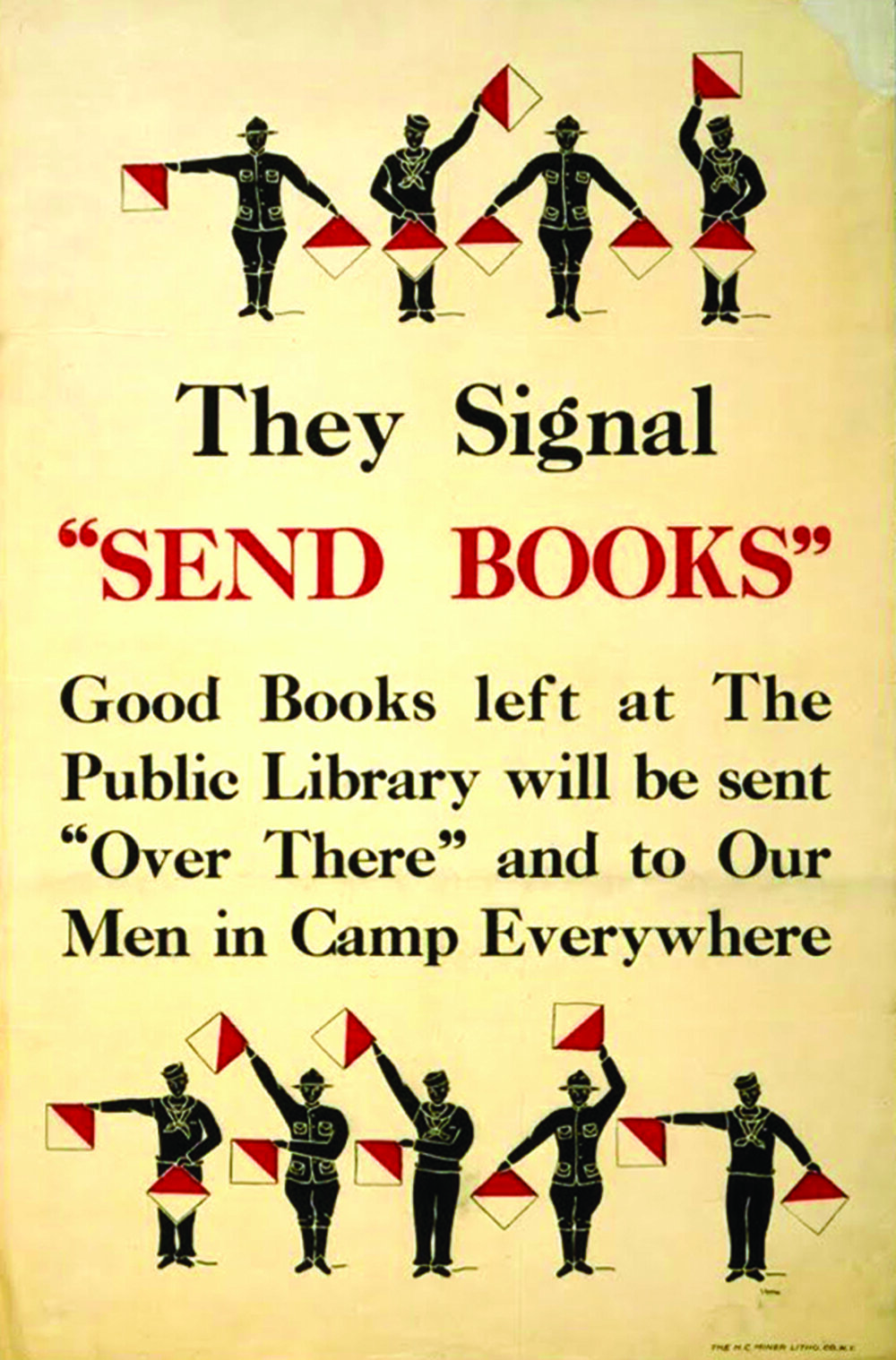

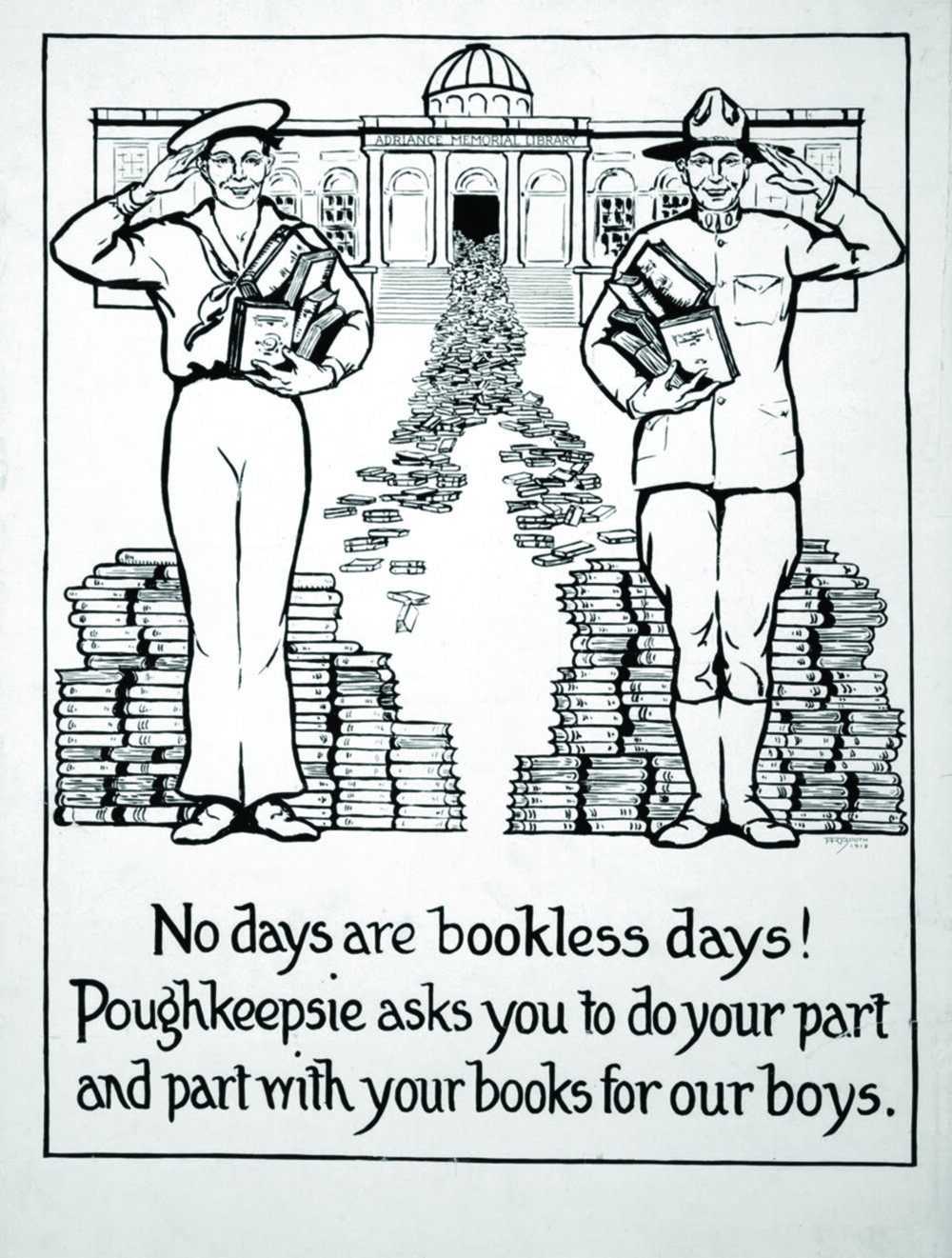

One of seven service organizations associated with the War Department commission, the ALA set out zealously to accomplish its mission. Directed by Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, and headquartered in Washington, DC, the Library War Service recruited staff and volunteers; established regional dispatch offices; and produced bulletins targeted toward public libraries, urging them to serve as collection sites and providing such publicity materials as posters, booklets, bookmarks, and press releases. Library staff were encouraged to donate their own money through the “Dollar-a-Month-Club”; the public was asked to place one-cent stamps on magazines and drop them into a local mailbox for delivery to soldiers.

Librarians promoted the program as making soldiers smarter and therefore better fighters, by equipping them with up-to-date technical materials and political works that explained the aims of the war. Reports from the camp libraries themselves suggest that the program served more varied desires and interests.[v] Officers and soldiers indeed sought military manuals, engineering and scientific guides, histories, and war narratives. In addition, they requested materials that would expand their outlook--travel books, guides to French language and culture, atlases, astronomy books, religious and inspirational books, plays, and poetry collections. Some wanted books on vocational subjects, such as bookkeeping, especially as the war drew to its close. And many opted for a good story, asking for such writers as Twain, Poe, Kipling, O. Henry, London, Tarkington, Conan Doyle, and H.G. Wells. Still others, unfamiliar with the very concept of a library, asked camp librarians, “How much does it cost to borrow books?”[vi]

One aspect of the program was not publicized, although word did leak out to the press: the ALA’s compliance with the War Department’s demand that certain titles be removed from circulation. A total of 80 books, deemed as pacifist, pro-German, or “salacious,” were banned from dispatching posts and library shelves.[vii] They included Understanding Germany, by Max Eastman; Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, by Alexander Berkman; and Open Letter to Profiteers: An Arraignment of Big Business in Its Relations to World War, by Scott Nearing.[viii] Upon learning that works by Zola, de Maupassant, and Daudet had been withdrawn at a New York sorting station, a Detroit journalist captured the fundamental irony: “This is supposed to be war for democracy. The fundamental theory of democracy is that the people—not the superior people, but all the people—have the right to rule themselves…. [A] man fighting for democracy has a right to choose his own reading matter.”[ix]

For the soldiers, the camp libraries offered havens for quiet, reverie, and study. A librarian looking back called the program, “the biggest experience I have ever had.”[x] Yet even as the program boosted soldiers’ morale and instilled pride among librarians, its operation reflected the fears and prejudices of its time: qualified black and German-American applicants seeking employment were turned away, and women were initially barred from serving as camp librarians.[xi]

After the war, the program’s functions were transferred to military departments. Its legacy includes the establishment of permanent library departments in the army, navy, and Veteran’s Bureau and the founding of the still-thriving American Library in Paris, built upon a collection of books assembled by the Library War Service and bearing the motto “Atrum post bellum, ex libris lux” – “After the darkness of war, the light of books.”[xii]

…

[i] Charles B. Alexander, “Address of Welcome,” Bulletin of the American Library Association, v. 12, no. 3 (Sept. 1918), 49-50.

[ii] Arthur P. Young, Books for Sammies: The American Library Association and World War I (Pittsburgh: Beta Phi Mu, 1981), xi; American Library Association website, accessed Jan. 16, 2016.

[iii] Quoted in Young, Books for Sammies, 10.

[iv] Chalmers Hadley, “The Library War Service and Some Things It Has Taught,” Bulletin of the American Library Association, v. 13, no. 3 (July 1919), 107.

[v] For information on reading preferences, see Young, Books for Sammies, 46-47; Theodore Wesley Koch, War Service of the American Library Association: Books for the Men in Camp and Overseas (Washington, DC, Library of Congress, ALA War Service), 10, 18-25.

[vi] Quoted in Koch, War Service, 16.

[vii] Young, Books for Sammies, 53.

[viii] Ibid.; see pages 109-113 for a complete list of banned titles.

[ix] Ibid., 52.

[x] Charles H. Compton, “What Then?” Bulletin of the American Library Association, v. 13, no. 1 (Mar. 1919), 6.

[xi] Young, Books for Sammies, 33-34.

[xii] American Library in Paris website, accessed Jan. 18, 2016. The Library War Service program also set a precedent for the Victory Book Campaign during World War II, which in turn led to the creation of the Armed Services Editions paperback series. For a study of these programs, see Molly Guptill Manning, When Books Went to War: the Stories That Helped Us Win World War II (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014).