Ye Ghost Ship

Posted by Gunnar Rice on May 8th 2020

An hour before sunset, after a stormy June day, in the year 1648, a crowd of colonists from the very new town of New Haven stood at the shore to watch a ship sail into harbor. While many had hoped, after a year and a half most had stopped praying for the safe return of its seventy passengers—and started praying for an “account” that would, as the Reverend James Pierpont explained, “let them hear what [God] had done with their dear friends.”

This ship, which now miraculously sailed against the wind, and which rode not on the waves but in the clouds, was, these Puritans believed, that hoped-for account. God, in his great mercy, had sent them a ghost ship that wouldn’t simply tell—but would actually show—what had happened to the vessel on which they’d staked so much.

This story, of the legendary Phantom Ship, begins not with this haunted hull, but years earlier, with an empty harbor. Founded by “men of traffic and business” in 1639, New Haven had in its first years nonetheless suffered a series of failed trading expeditions to the West Indies. By 1646, leading merchants, “gathering together all the strength which was left ‘em,” contracted a Rhode Island builder to construct a “Great Shippe” that would carry all their tradeable goods to London. But the ship, which was either poorly or hastily built, sailed, noted one contemporary, “very walt-sided”—that is, so unevenly that it would, its captain George Lamberton often noted, likely “prove their grave.”

The atmosphere was certainly funereal on the cold January day when the nameless ship disembarked: for three miles, as an advanced crew cleared ice, the 150-ton hulk inched through the harbor to the sound of onlookers’ “fears, as well as prayers and tears.” The Reverend John Davenport is said to have addressed the dismal company in prophetic terms: “Lord, if it be thy pleasure to bury these our friends in the bottom of the sea, they are thine, save them.” Writing with the benefit of hindsight, the chronicler William Hubbard even more fittingly described how the ship’s loss at sea affected the New Haven merchants: “with the loss of it,” Hubbard noted, “their hope of trade gave up the ghost.” On that June day, almost eighteen months later, this metaphorical ghost had, many New Haven faithful believed, returned home.

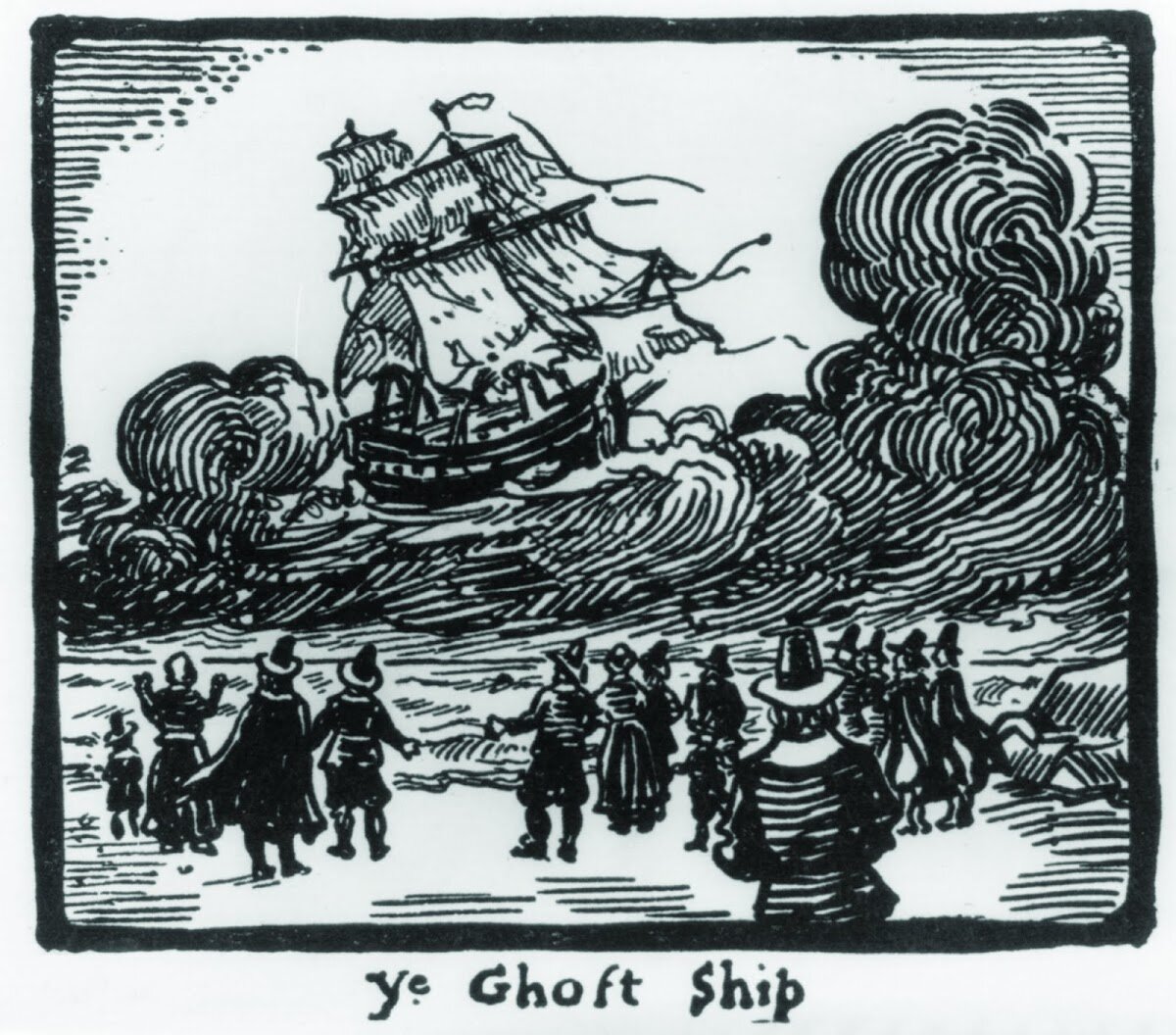

While many written accounts of the Phantom Ship have survived, the wood engraving (see above) is the only known contemporary image. Accordingly, many of the details Pierpont, Hubbard, and later chroniclers “received from the most credible, judicious, and curious surviving observers” appear also in this undated engraving.

“The ship approached so near they could throw a stone into her,” writes Pierpont of those observers of the Phantom Ship, whom the anonymous woodcut indeed depicts alarmingly nearby. “This was seen by many, men and women,” and even “children cryed out,” Pierpont notes, and indeed men, distinguished by their Pilgrim hats, women, by their bonnets, and children, by their small stature, all crowd into the foreground. “Her canvas and colors [were] abroad,” Pierpont notes of the ship, and her sails and flags indeed appear fully unfurled. Even the “great smoke” into which observers said the ship eventually “vanished” seems to arise, as contemporaries noted, “from the side of the ship which was [away] from the town.”

The engraving thus captures the moment just before the Phantom Ship disappeared into the “smoke” and then the sea—in what the onlookers believed was a representation of the ship’s “tragic end.” Those looking for the full picture of this encounter might consider filling the engraving out with lines from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Phantom Ship” (1858), which delineate as only poetry can how

...The masts, with all their rigging,

Fell slowly, one by one,

And the hulk dilated and vanished,

As a sea-mist in the sun!